Around the corner from my grandmother’s house in Burlingame, California was an ice cream and candy store called Preston’s. I walked there often with my grandmother for a treat and, to this day, I think of her whenever I see peanut brittle. On this particular day in about 1973–I’m guessing I was around four–I was with my mother who had just picked me up from Grandma’s. We went to Preston's for ice cream. Standing in line, I pointed to the lady’s cone in front of us and asked my mom, “What’s that green one?” “That’s mint chip,” my mom told me. And from that day on, mint chip it is.

Michael Pollan wrote in The Omnivore's Dilemma that our food preferences are shaped by culture, which actually means “the food your mother made.” I’ve always found this an apt and hilarious way to describe culture. My mom didn’t “make” mint chip ice cream but she introduced me to it, and fast forward 50+ years, it’s still my numero uno, absolute favorite flavor.

A few years ago, I retired my daily wine habit, and my sweet tooth came roaring back. My go-to treat was, you guessed it, mint chip ice cream. By this point, my tastes had become more discerning and I preferred white minty ice cream with irregular chocolate chips. Tillamook mint chip ice cream fits this bill completely and became a regular purchase from my local Andronico’s grocery store.

One day, it wasn’t in stock. Fine. I probably shouldn’t eat so much ice cream anyway. But then this went on for weeks. When the checker asked me if I found everything I was looking for, I finally spoke up about the missing flavor. He said he’d pass my request along to the manager. Weeks went by, and still no Tillamook mint chip. I resorted to an inferior brand.

In line, I brought it up with the store manager, Johnnie, and a look of dismay crossed his face.

“I will try but I don’t know if Corporate will let me reorder it,” he says.

“Well, you’ve always had it; it’s just in the last few months it hasn’t been stocked. I think it’s just a glitch,” I say. “Maybe when the Tillamook delivery person comes you can just tell him to put some mint chip ice cream in the case.”

Then Johnnie blasted through my naivete and revealed a bit about the underbelly of inventory control. He explained that managers aren’t allowed to change or customize the inventory for their store. If they do, they risk getting in trouble with Corporate. At night, when the store is closed, inventory workers (who the daytime people never see or interact with) take pictures of the shelves and send them to Corporate. In this case, “Corporate” is Albertsons, which owns Safeway, which owns Andronico’s. If the photos show unauthorized products, the manager could face repercussions. His face showed defeat, the tone of his voice registered disempowerment.

Let’s pause this epic saga to notice the intersection of customer experience, employee empowerment, and corporate control idiocracy. As a customer, I won’t get to buy what I want because employees aren’t empowered to act locally and use their disccretion to fulfill my request. The manager loses face with the customer by revealing his lack of authority and decision making autonomy. In the low-margin grocery business, Corporate has decided that the path to efficiency and profitability lies in micro-optimizations, tight inventory control, and a surveillance culture.

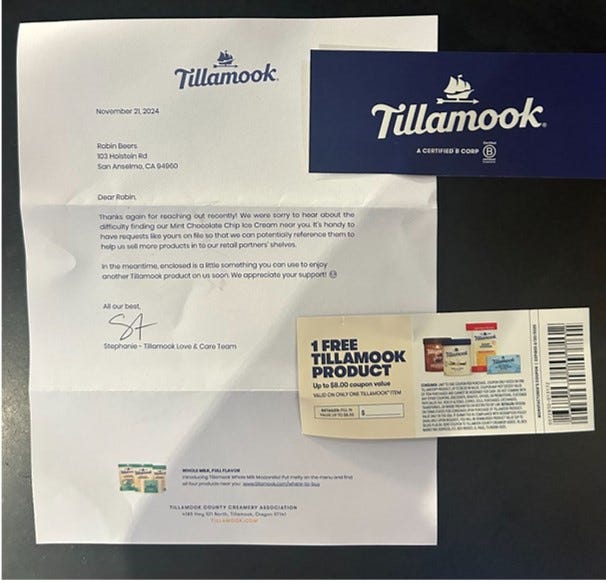

A normal person would be annoyed and go on about their life. An organizational psychologist (me) goes home and sends emails to both Tillamook and Andronicos. Tillamook sent this lovely response in the mail on thick letterhead and included two coupons for free ice cream, which I promptly used for mint chip at a competitor not owned by Albertsons.

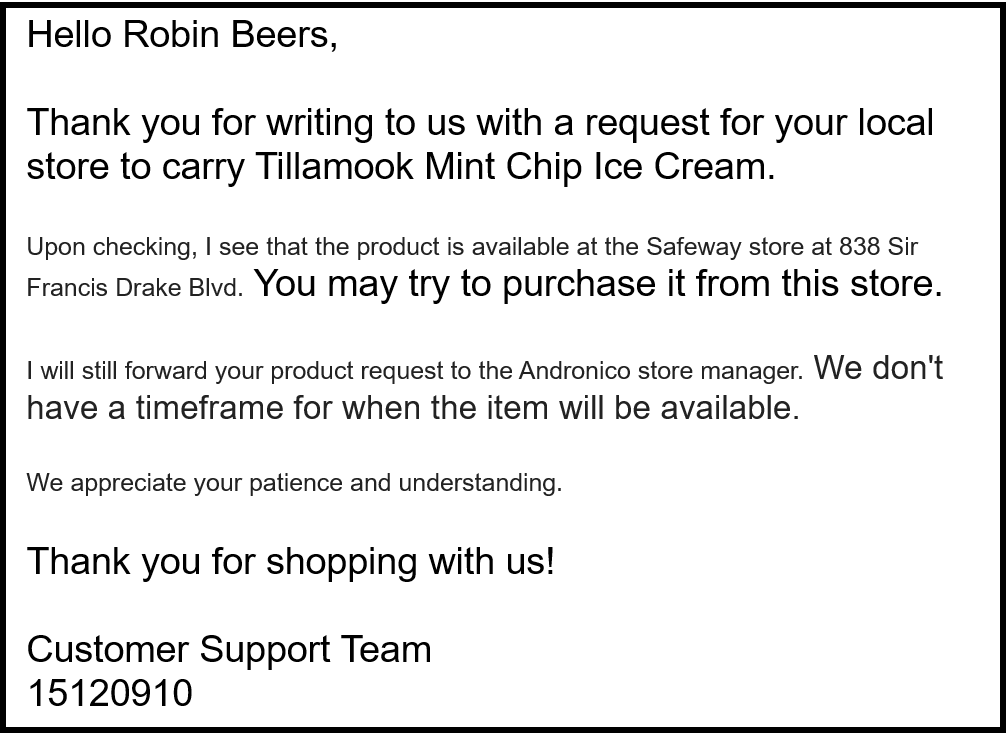

Albertsons, however, responded with a generic, cut-and-paste email unintentionally containing different font sizes, suggesting I shop at a different store they own but that isn’t part of my weekly shopping routine. From a customer experience standpoint, this shifted the burden to me to meet my own needs while conveniently keeping the profit in their ecosystem. They also promised to forward my request to the store manager. Why? If the manager were empowered to meet my request, we wouldn’t be having this email exchange.

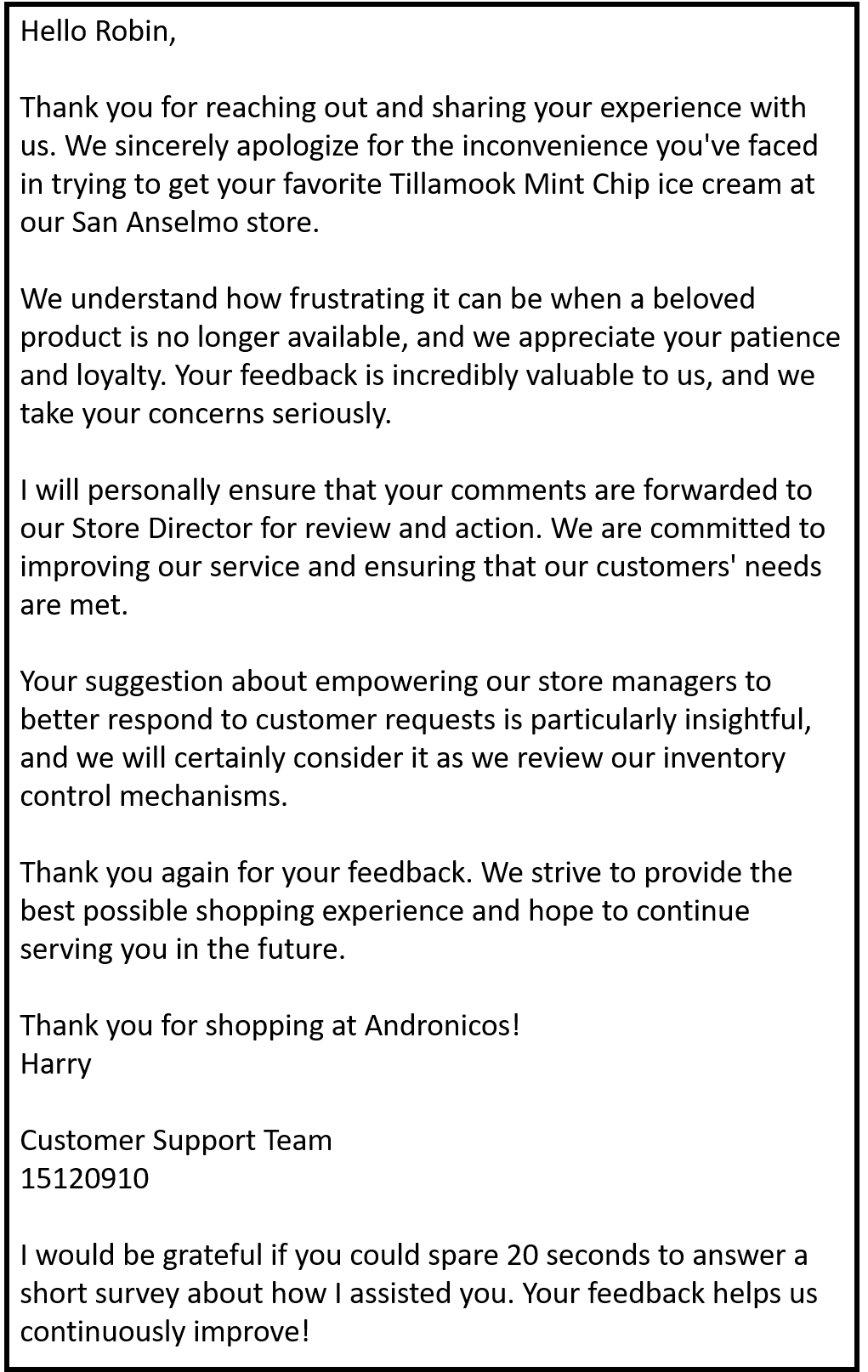

Now I’m just having fun and write back to say that I’m unsatisfied with this response. A week later I get this much better response from Harry, with whom I’m on a friendly, first-name basis.

This more detailed and care-filled response from Harry at Albertsons did feel much better than the first email but I'm still without mint chip at my usual store.

On a particularly busy shopping day, store manager Johnnie opened another checkstand and called me over from standing in a long line. I gave him a brief rundown of my efforts. An expression passed over his face that was at once a combination of appreciation, fear, and something like, “this chick is weird.”

After I reassured him I hadn’t used his name in my emails, he told me he was grateful I was pursuing the issue. He shared more stories: an elderly customer longing for a discontinued pretzel and offering to buy an entire case, multiple requests for Shake ‘n Bake which they no longer carried, both requests he’d been powerless to fulfill.

Then he said something that touched me deeply; it is the reason I’ve devoted my career to improving customer and employee experience:

“I really love this place, and it hurts me when I can’t make things right for customers.”

I mean, isn’t that what any company would want in an employee? Why would it put processes and systems in place to obstruct that pride and love? When employees or customers use the word “love,” executives should sit up and listen. (Check out Utibe Bassey - Love as a KPI). Love is where passion, loyalty, commitment–and, yes, profits—live.

Here is what really bugs me about this: Albertsons approaches inventory management from mechanistic perspective, prioritizing rigid control and uniformity over flexibility and trusting managers to use sound judgement to meet customer needs. Employees are surveilled by faceless entities empowered to flag discrepancies and penalize them. Where is the reciprocity in this relationship between company and employee?

In the near future, AI will likely play a central role in grocery store inventory management, potentially eliminating human inventory workers. Will AI enable greater responsiveness or reinforce rigidity? The answer depends on the assumptions baked into the system. If the core priority remains uniformity and top-down control, the technology will only amplify the current shortcomings. Different assumptions yield different strategies, process designs, and business outcomes. As Steve Jobs famously said, “Design isn’t how it looks; it’s how it works.”

Great process design, whether analog or technology-enabled, starts with three principles:

See the Whole: A systems approach lets you see the interactions between parts and how they affect the whole. Does the solution work for all stakeholders, or are there winners and losers?

Unmask assumptions: Articulate assumptions explicitly. Is the goal cost-cutting efficiency, customer experience, or both? If both, how can they harmonize? If only one, what are the trade-offs?

Recognize socio-technical dynamics: Human and technical dimensions are intertwined. Analysis is required to account for their complex interplay. Think beyond the spreadsheet. Have you considered how your solution plays out in real life? Can you pilot-test it to refine and learn?

The best business and organizational solutions reconcile human needs and technical efficiency, challenge underlying assumptions, and take a holistic view of the system.

In the Industrial Era–which still dominates many leader’s thinking today–factories gained efficiency and profitability through breaking wholes into smaller and smaller parts. But we no longer live in a world of discrete inputs and outputs. Today, in a world of perpetual upheaval and complexity, we must simultaneously pay attention to interdependencies and dance with shifting dynamics.

While I’m waiting for my mint chip ice cream to be restocked, I’d love to help your organization design strategies and processes that work for the whole. Let’s set up a 30-minute discovery chat to start figuring out how to put the pieces back together again.

I think this is your best article yet, Robin. What's more human than ice cream? I too have found system design object lessons in grocery stores. Like when I realized that the wall of granola at Gus's was too much choice; too many choices is the antithesis of simplicity. My research led me to the European small store model where grocers *curate* based on their intimate knowledge of customer preferences. I think the problem is how to scale, operationally, that intimacy, that love. If we can keep you lessons in mind, especially to recognize socio-techno dynamics, then there's hope!

I can’t agree with your favorite ice cream flavor but I enjoyed reading this. It made me think about my first ever job. When I was in high school I worked in a grocery store (O’Malias). They prided themselves on providing excellent customer service, including ordering specialty items at customers’ requests. So many people shopped there for that reason even though it was pricier than the big chain store. There’s no substitute for the feeling one gets when they feel heard and taken care of. I resonate with the manager so much because being able to provide that level of care feels just as good as receiving it.